Nearly two years later, in 1941, a BBC representative arrived searching for bright young students as potential employees. Essential, he explained, to replace staff enlisting in the Armed Forces. Why they selected the Hull Technical College to look for budding engineers I will never know.

It was an extraordinary day in the autumn of 1941, well before my 16th birthday, when I received an invitation to attend an interview. The Principal of the college said it was for a vacant position entitled 'Youth in Training'. It certainly didn't sound very important or exciting at the time, but a career with the BBC impressed an image of sophistication in the mind of a young fellow still in the throws of learning. Sure would impress the girls, I thought.

"I understand that you are a pianist with honour certificates. And a first-class knowledge of music theory, too," said the BBC representative.

"Y-yes, Sir," was all I could quietly muster as a quivering reply. How did he know all the details?

He recommended that I ask my parents about service with the BBC because a clause in the contract stated that employees are subject to transfer at anytime and to any posting in the UK.

That evening, my mother expressed her deep concern about the idea of her son leaving home, especially at such an early age. Dad thought it was a very good idea believing that it would offer ample potential for future success.

"Did they say where they wanted you to work?" asked Dad.

"He mentioned somewhere in Hull but didn't say exactly where."

"Not to worry, lad, you're bound to make a go of it," encouraged my father with sure-fire enthusiasm. Mother continued to express her anxiety about all the risks involved if one of her dear sons left home so soon, but reluctantly agreed.

At the beginning of the war, German bombers used BBC radio transmitters for navigational purposes to home-in on vital targets. To overcome this possibility the BBC installed a 'Group H' transmitter, each with a power output of 50W - 1kW, in major towns and cities. They all operated on the same frequency of 1474 kHz. This confused German pilots as to the exact location of any one transmitter. To keep installation costs low, engineers suspended aerials from water towers, chimneys and similar tall structures instead of building new support masts. To avoid German misuse of the high-power transmitter signals, these primary stations could close down when a local air raid became inevitable. On the other hand, the small H group stations continued to broadcast the Home Service unless enemy aircraft approached within 30 miles.

Pity the poor engineers and assistants who staffed these stations for 24 hours a day to ensure broadcasting of essential information. Would you believe that local authorities could, if needed, broadcast special announcements from the station, if the Germans ever invaded our shores!

On September 22, 1941, I travelled via two bus routes from the west side of the City of Hull over to Holderness Road on the east side. At nine o'clock in the morning, on my first day of work, I reported to the Senior Engineer in Charge of an H Group station.

Arriving clad in my best suit, I felt very important as I mentally flourished the ambiguous title of a BBC 'Youth in Training'. Simultaneously, I began to amass a serious ambition to become a recognised BBC engineer overnight, or so I thought.

Not surprisingly, I found the transmitter equipment neatly installed in a building adjoining a very high chimney. A rack of control equipment stood in one corner while a small office furnished with a desk, chair, table lamp and telephone occupied the opposite side. In complete isolation, the small transmitter cage rested on a long wooden table in the centre of room and towards the back wall.

Within an hour, and to some dismay, my first task included sitting at a desk and watching, no, ensuring that a white needle in a meter only flicked backwards and forwards between assigned marks identified with a series of numbers. Later, the engineer on duty remarked that it was very important to verify, occasionally, that the transmitter was sending its multitude of electrons along the aerial wire, through the wall, all the way up to the top of the chimney and into outer space.

Using slight of hand or a concealed technique to create super-natural illusions, he prepared to demonstrate his 'party piece'. In a resourceful and classic manner, he held a small neon bulb between his index finger and thumb. Then, slowly, he moved it towards the aerial wire (feeder). At about one inch away, it suddenly lit up like a Christmas tree.

"Oh, very clever!" I mused, "Most impressive."

With a broad grin on his face, he repeated the act confirming all was well.

Now he didn't know that I was already familiar with the theory of radio frequency radiation but the revelation of its effects certainly impressed me. Wireless World magazine occasionally published all the answers but this was youthful fascination.

To illustrate that it would do me no harm he let me hold the bulb, but I pretended to display an element of fear. At that point, we enjoyed a mutual sense of humour. He was a great guy and an excellent teacher. I learnt a lot about broadcast technology and in a very short time.

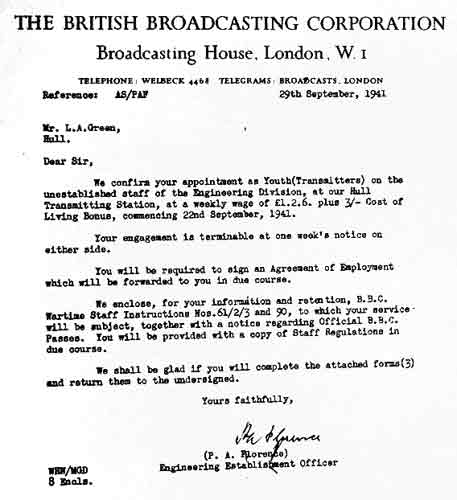

True to form, by the end of the second week, I received an official envelope from Broadcasting House in London. It contained a multitude of employment papers, agreements, regulations, staff instructions, and a reference to secrecy.

It is fascinating to bring to mind that for more than sixty-five years I have treasured that badge as though it was made of gold. Today, it continues to rest serenely inside a bank's safety deposit box.

It is interesting to read old correspondence. The first BBC letter outlined my weekly remuneration of one pound, two shillings and six pence plus a cost of living bonus of three shillings. I always wondered if the BBC would rescind the latter amount when living conditions improved after the war.

Unfortunately, after a month or so, the daily work routine, except for studying, soon turned to boredom and escalated into partial disinterest.

Throughout the winter, there were many occasions when I wore a 'tin' helmet while riding a bicycle through late night air raids. It was an exuberant determination to make sure I arrived on time for any assigned shift work. Invariably, it was an hour's exhausting journey stopping, when necessary, to find shelter. Occasionally, on the return journey, I had an inherent apprehension that without telephone communication you never knew what to expect when you arrived home, in particular the next morning.

Although time spent at the transmitter station was extremely tedious for an active mind, I certainly gained a fair amount of technical knowledge, more so about the programme content of broadcasting.

After a while, I became restless and politely asked why, in the early stages, did the BBC express interest in my music qualifications yet had almost forgotten about them a few weeks later. Discussing the subject with the Chief Engineer, he said he would investigate and let me know the outcome.

Afterwards, in fact it was in the early spring when I received a letter of transfer. It contained instructions to report to the E.I.C. of the BBC in Manchester. Returning home that day, I anticipated an in-depth discussion about leaving for greener pastures but it was not to be.

"I'm to report to Manchester at the end of the month," I announced with youthful bravado.

Almost immediately, Ben, my younger brother, asked if he could have my bicycle. I said yes, only if I didn't have need to take it with me.

Mother posed the first question, "You'll have to find a place to live?"

I quickly explained, "No problem, the BBC says they can provide staff billeting at a reasonable rate."

Mother didn't like that idea. She remembered having friends living in Manchester who may be able to take care of me. Dad said he would write a letter.

Odd thoughts immediately flashed through my mind. Do I need someone to take care of me? Hell, I'm sixteen years of age. Do I really need taking care of? Too bad, don't argue, I had no choice.

A week later, the couple replied inviting me to stay with them. With tenancy organised, I awaited the appointed day to leave home for 'distant' lands. Suddenly, and with concealed anxiety, I became apprehensive about entering into an unknown world. For the next few days, I did my best to make sure that my inner feelings were neither visible nor heard.

"We'll take you to Manchester," said Dad a week before the day of departure.

Oh, no! I was about to rebel when they offered to chaperone me across the Pennines to Manchester.

"We'll just make sure you are settled down over the weekend before you start work," advised Mother.

"Do you really have to, Mum?"

"It's for your own benefit, Leonard. It's a weird and wonderful world out there."

I didn't argue. She was right when she said, "For the first time in your life you'll find yourself making each and every decision all on your own. It may be a painful process."

1942, and in Manchester at a tender age of ignorance, I had an enjoyable time at the BBC - well, almost. In those early days, learning the 'ropes' amounted to participation as a pseudo actor by interspersing sound effects, on cue, into evening dramas and Children's Hour programmes. Encountering split second timing, using this method of creativity, was nothing less than a precise art form of entertainment - especially valuable later in life when involved in radio comedy shows with Norman Evans, Ted Ray, Charlie Chester and others.

I recall one unforgettable episode. My contribution was to insert sound effects into a late evening drama - and in those days it was 'live', as they say, on air! One method of introducing sound effects before a microphone was called 'Spot effects' - generally made by hand - compared to other more continuous sounds inserted from vinyl records. The latter were reproduced on special gramophone machines, colloquially called 'grams' located in the control cubicle.

My first embarrassing incident related to one dramatic moment when the 'villain', exhibiting a confrontational disposition, entered aggressively through the 'living room' door. At the appropriate moment and on cue, I snapped the door open; waited for him to complete his singular belligerent line then, timely and following the script, slammed the door shut. Well now, the physical placement of the simulated but practical door must be visualized to appreciate my faux pas and the inevitable aftermath.

I thought my world had come to an end.

On the other hand, such disruptions, I was politely told by colleagues while exhibiting a fair amount of hilarity, were just part of the learning game - not so, according to the producer's somewhat reserved opinion at the end of the programme.

Meanwhile, this and many other enlightening experiences, sometimes exasperating moments, were suddenly offset by a transfer, for a second time, to a small hamlet called Wood Norton close to Evesham and not far away from Birmingham.

So, what happened to my original aspirations wherein I anticipated exploitation of musical knowledge and talent? To my chagrin, I was told; later, maybe later - in the meantime, a reassignment was in order to acquire recording skills.

We move on a decade and Len, by now a family man, recounts a tale about a gap in the Home Service schedule...

Late 1951 and a few weeks after moving into our newly purchased suburban house near Manchester, I sat at the breakfast table anticipating advertised scrambled eggs on toast. In those days, it was a rare pleasure to be presented with more than one at the same time-usually it was a singular edition, boiled.

As my wife, Rita, approached the table carrying a plate supporting a small amount of egg and tiny slices of toast for our two year old son, Ian, she looked across in my direction featuring an odd expression; nearly a glare.

"Something wrong?" I asked.

"Very funny," she replied, walking quietly back to the kitchen.

"What's funny?" I called.

Returning to the table she continued, "I'm wondering why you're sitting here gazing at the ceiling-and at this time in the morning?"

"Because you called to say that breakfast was almost ready."

"But I called you to come downstairs nearly an hour ago! Twice, in fact. What takes you so long?"

"I still don't understand."

"See the time? It's past eight o'clock."

"So . . ."

Last night you said you had to be at work first thing in the morning. That's why I called you earlier on."

"My God, so you did!"

"Watch your language, children present." I dashed across the room to switch the radio on. Rotating the dial to the Home Service I heard a familiar voice announce, in what may be described as a fairly unforgiving overtone:

"Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. This is the BBC Home Service. The time is now five minutes past eight. We regret, due to circumstances beyond our control, that we are unable to bring you Programme Parade. In the meantime we will play some light music."

My stomach dropped a mile.

"Strewth! Now I remember, I agreed to play its pre-recording this morning."

"Well, well, should we all head for the nearest breadline?" admonished Rita with an element of sheer distain.

"Better scoot. Sorry about the eggs."

"Sit. Eat your breakfast, the damage is done."

"No, gotta go."

"I said; sit. Now, while you're eating, better tell me the whole story." Reluctantly I obeyed while Ian remained silent; helping himself to everything on his plate and whatever else was in close range on the table, childishly oblivious to the conversation.

"I shouldn't be so charitable."

"I'm waiting! Explain."

"Yesterday afternoon, Ken mentioned that his dentist had a cancellation in the morning. He asked if I would cover for him and play the pre-recorded Programme Parade, just after eight o'clock.

"And?"

"Well, of course, I agreed."

"Do I have to drag the rest of it out of you?"

"No, but after I finished with the late night drama, I cleared up, put the disc in the office drawer, and came home. If I had thought about it I should have left it in the continuity suite rack. Obviously, when I arrived home just before midnight last night I must have forgotten about it."

"That's really no excuse, is it?"

"Oh, I guess not. I'd better go and face the music. In any case, I'm booked for a Children's Hour rehearsal in an hour and a half."

"It's going to be a very interesting day; isn't it, Len?" posed Rita, being the only adverse comment she made to end the conversation. I quickly finished breakfast, dressed, said my goodbyes and silently walked out of the house towards the bus stop.

"Have a good day, dear," she called standing nonchalantly cross-legged at the front door, "Maybe today you'll be home a little early for a change." By her side I noticed she was holding Ian's hand while I vanished sheepishly around the corner.

"To hell with this nonsense," I mumbled under my breath as I stood waiting for the bus, "That's it! I've decided to emigrate to a far-off land!"

Len also worked for the BBC in Wood Norton, London and Bristol. Following service overseas with the Royal Signals/Intelligence (Bletchley Park out-station) he emigrated to Canada. There he joined the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation during the introduction of television. Later he served as Director of Engineering for Film House Ltd., a private motion picture company and as a Director of the Technical Branch of The National Film Board of Canada. He finally retired after ten years consulting in all three vocations. Lenís varied lifestyle is portrayed in his autobiography entitled "Take a Risk."