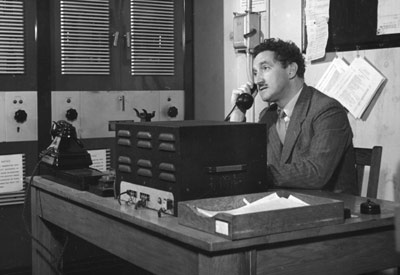

Gerald Daly (right, in the transmitter room) was the prewar Engineer in Charge of BBC West Region and in 1974 he wrote a letter to Patrick Handscombe (a History student at Bristol University who was researching the railway) describing his involvement in the project to build broadcasting facilities in the tunnel. Patrick has kindly made this letter available, together with several photos taken in March 1942, and it appears (slightly edited) here....

The Bristol Archives gave me the idea of using one of the disused tunnels [of the old Bristol to Avonmouth railway] as a shelter for a broadcasting station, because they themselves used one of these tunnels to house their archives during the war. I used to pass it periodically on my way home and wondered what it was.

The idea was to provide a shelter for the several hundred broadcasters then in Bristol. In addition to the original regional staff there were many who had been evacuated from London. The Symphony Orchestra was under the charge of Sir Adrian Boult and with them had come the whole London Music Department. The London Variety Department was under its director John Watt, and there were also the Schools Department, the Religious Department and a number of administrative departments such as Finance, Listener Research and Filing together with libraries such as music, etc. Thus the region was swollen from a mere fifty or so persons up to several hundred, with all the facilities needed for broadcasting.

I came into the picture because, for my sins, I happened to be the Engineer in Charge of the West Region prewar. Also, as engineers are looked upon as the dogsbodies of the outfit, I was asked by the Regional Director Mr (later Sir) Gerald Beadle, to take on the job of organising and running the Air Raids Precautions work needed at the time.

I was also at the time very much concerned with the flimsiness of the shelters which we had prepared for our own small staff, namely the shored up basements of the old Victorian houses which were our regional HQ.

We had never expected to look after many hundreds of people - the only department which was supposed to be evacuated to Bristol was the Symphony Orchestra, the rest had come down without warning.

The most exposed to the bombing were Sir Adrian Boult's Symphony Orchestra involving nearly a hundred personnel. At first we had rented the Clifton Spa Hotel and its ballroom to accommodate them, but to our horror, and just before they arrived, Imperial Airways requisitioned the whole hotel over our heads. The BBC had no powers of requisition not being under the aegis of the government.

We had great difficulty in finding alternative accommodation for such a large orchestra but eventually the Co-Op Wholesale people came to our rescue (I joined the Co-Op forthwith in gratitude) and rented us their large hall and offices down in Bristol Centre. This was all right until the Nazis conquered France and Bristol came within easy range of enemy bombers. So I looked for a safer place than the Bristol Centre.

The old railway tunnel where Bristol archives were kept seemed a likely place for the orchestra from the shelter point of view, but how would an orchestra sound in the narrow confines of a railway tunnel? We decided to try and Sir Adrian assembled about sixty players in the old tunnel. A record was made and to our amazement the musical quality was far better than expected. So we decided to put the matter to my bosses in London. The Director General, Mr (later Sir) Frederick Ogilvie, came down a week or two later and I took him through the length of the tunnel holding up an Aladdin paraffin lamp. Alas, however, there had been an unpleasant raid on Bristol and particularly Avonmouth (about six miles away) and the tunnel was crowded with refugees, so we could hardly move. The city authorities offered to get rid of them, but we could not take it and gave up the idea of using that tunnel.

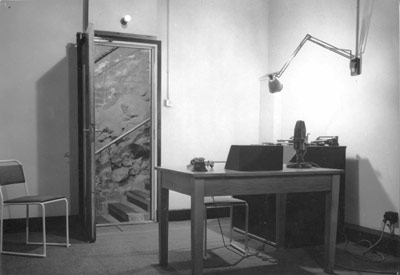

The west stairway looking down, with the Transmitter

Room doorway on the left and the main extract ducting overhead. The

corrugated iron lining to the bare rock and brick-lined tunnel was a

BBC addition.

I was at once interested in the rest of the tunnel, especially when they confirmed that there were about sixty feet of rock between them and the surface.

Although there was some opposition, the idea seemed to have general approval. The need for accommodation no longer mattered as far as the Symphony Orchestra was concerned for the bombs had got too much for them in Bristol and they fled to Bedford. The Variety department had also left Bristol - first of all we had transferred them to various halls and hotels in Weston Super Mare, twenty miles away, and they had in turn fled to Bangor in North Wales. It was said that Hitler made a point of following the BBC's Variety department wherever they went because of the funny, but nasty, things the comics of that department said about him on the air. Tommy Handley, Arthur Askey and Kenneth Horne were among the main culprits.

So the need for large halls had gone, which made the decision for the Tunnel station easier. Before a decision was reached to go ahead, there were various meetings in Bristol between the London officials concerned and ourselves. I well remember the final meeting when the decision was made to go ahead with the project because it lasted all night.

These meetings were held in the Regional Director's office - Mr Jely de Lotbinière - and about three a.m. the latter said that as a decision was now reached and the discussion would now be largely technical, he would go to bed. We all had our beds in our offices during the war. We were amused because when Lobby, as we called him, got into his bed, owing to his height, about 6'6", his feet - bare - stuck out at the bottom. That impressed the meeting on my memory.

The next step was to get the owners of the Tunnel together and to get their permission. There was a snag here because the actual ownership of the now disused Tunnel was complicated. We had hitherto dealt with the local city authorities, particularly the City Engineer, a Mr Bennet.

The CRR was built and operated by the Clifton Rocks Railway Company. The Bristol Tramway and Carriage Company took it over in 1912 (the Chairman was Sir George White who had also started the Bristol Airplane Company). But they had leased the property from the Bristol Merchant Venturers, an old city concern going back to the Middle Ages and responsible for slave tradery, pirates and privateers and voyages of discovery to America. Cabot was I think financed by them. Also concerned with the Tunnel premises were the Downs Committee of the Bristol Corporation, who controlled any activity at all to do with Bristol Downs - a very upstage crowd indeed.

With the help of the Bristol local authority, we invited everyone concerned whom we could find to a meeting in the actual tunnel to get their approval of the BBC scheme. I well remember this meeting. Representatives of the various people I have mentioned turned up together with others interested. The principal one of the latter was Sir Hugh Ellis, the Regional Commissioner of the West of England (he would become virtual dictator of that area should there be an invasion and the main London government out of touch).

I remember we sat on some odd chairs collected for the occasion in the lower part of the Tunnel, with water dripping down on the heads and knees of these distinguished gentlemen. The place was partially lit by one paraffin Aladdin lamp, and the surrounding gloom was quite eerie. The three old trams at the bottom of the incline could be dimly seen in the shadow. The discussion went on through the afternoon from 2 to 4 sort of thing - everybody seemed to want to have their say. At last Sir Hugh Ellis said "I'm fed up with sitting here with the drips coming down on my bald head - has anyone any valid reason for not letting the BBC have their broadcasting station here in the Tunnel? If not I agree to the idea and the meeting is at an end."

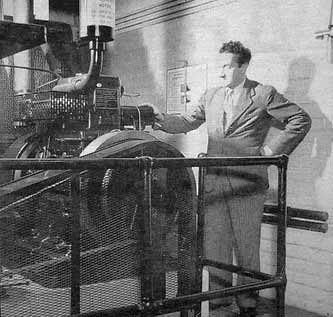

An RCA 'H' Group transmitter in the Transmitter Room.

At the top would be the transmitter room housing the local Bristol transmitter for the town and environs, a communications transmitter to keep in touch with the rest of the BBC stations up and down the British Isles in case the telephone links were disrupted, and a spare transmitter.

Underneath this would be a recording room with various types of recording equipment and space to store records.

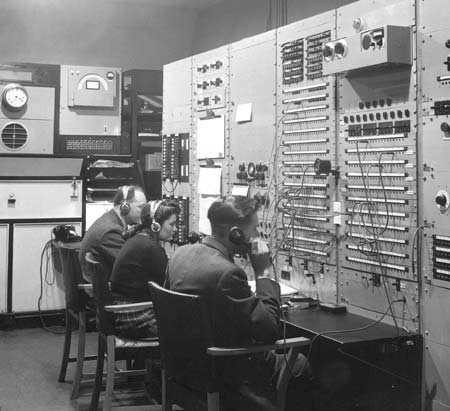

Next would be the main control room with equipment and landline terminations to other BBC stations and numerous transmitters, including overseas services. We were transmitting programmes in about forty different languages all over the world.

Under this would be the canteen, stores and power room to give us our own power if the mains electricity failed and we were cut right off.

The emergency exit from the Control Room down to the

Diesel Generator Room, seen below. There was a similar arrangement in each room.

A good deal, of excavation had to be carried out on the solid rock and a special tunnel engineer was employed to do this particular work.

The planning was done by ourselves, i.e. The Maintenance Engineering department and the Building department of the BBC. The cost was £20,000.

The whole project took six months to finish and I moved the main engineering staff down to the tunnel in 1941. Henceforth for the rest of the war this was the nerve centre of the BBC in the West of England. Through the Tunnel control room for the next four years passed all the programmes of the BBC to home and overseas. The engineers who were there permanently during the war were Q Fisher, Douglas Gibb, and F Dennis, Senior Engineers in charge of shift, while their staff including some girl engineers consisted of about four per shift of three shifts throughout the 24 hours.

We went back to the prewar control room in Whiteladies Road at the end of the war. We held on to the Tunnel for nearly another two years - we only paid a peppercorn rent to the Bristol Corporation for renting it. I think it was about £5 a year. Then we removed all our equipment and the City took it over - the chambers, of course, remain. (In fact the CRR remained a BBC "Deferred Facility" until 1960 - the author was probably reluctant to mention this at the time of writing - ed.)

A memory which still hangs around the back of my mind is the time when we were asked if Queen Mary, who had been evacuated to nearby Badminton, could see over it. It had been kept such a secret that we were surprised that she could ever have heard of it. Anyway she came along, but as she was getting on we thought that she would not want to climb the hundreds of steps to see into each chamber, so we arranged that we would tell her about it in the entrance hall.

When she came however she said she wanted to see it all and started up the steps. She climbed to the very top apparently without losing her breath, while we men panted behind her very much out of breath.

We maintained a permanent military guard over the tunnel throughout the war by means of our own BBC Home Guard Company of the 11th Gloucestershire Regiment. Well known broadcasters were members of this Company: Sir Adrian Boult, Stuart Hibberd, Uncle Mac and many musicians and variety stars of radio of those days. (For my sins and being as I say a local dogsbody I was Captain of the Company of course.)

Of all this massive handling of foreign languages in our time in the Tunnel, only one serious technical hitch came to my attention. A programme from the Arabic quarter in Cardiff was scheduled to go out to the Middle East. Afterwards the engineer in charge of the shift, one Arthur Fisher, came to me and said that some of the staff were slightly doubtful if the Arabic programme in question was true Arabic. One of the engineers was in Allenby's Egyptian Army in the First War, knew a few words and was doubtful. However we heard no more of it until some weeks later a Welsh speaking professor of English in Cairo wrote to say that he had heard to his surprise a programme on the BBC's Overseas Service in the Welsh language on Welsh piggeries. The professor pointed out

Apart from the control room operation at the Tunnel which was as I say, used throughout the war, most of the recording work was carried out there in the recording chamber (right). All recorded programmes were stored there too for safety's sake.

The Philips-Miller Recorder

The studio was little used as we had only one real emergency,

that was after a heavy raid when the city's water supply was blown up. The

Regional Commissioner appointed two Bristol citizens whose voices would

be familiar, a Mr Hindle (the City's Publicity Officer) and a Mr Wiltshire,

a solicitor and musician. They broadcast warnings about the water supply

on this occasion.

In the darkest period of the bombing of Bristol there was talk, in the case of invasion or complete destruction of London, of the Tunnel becoming the BBC's last ditch.

The lower station façade showing the ventilation

intake and outlets, the aerial mast for reception and the diesel generator

exhaust pipe over the car on the right.

I had discussed making the Tunnel into a still more secure place with my commander in Bristol - the military commander of the Bristol area. He had agreed that our prewar HQ in Whiteladies Road had little chance of stopping an enemy assault, but that the Tunnel was infinitely easier to defend and make secure. He said that I should do so but not let anyone know, not even my second in command, who was Stuart Hibberd the famous announcer. The trouble was that Stuart, an ex soldier, was mad keen on making the old HQ in Whiteladies Road into a veritable fortress, and sandbagged and barbed wired it so that one could hardly get out or in. And I could not explain that we had no intention of trying to defend the old place and that the Tunnel was really our wartime fortress.

Thanks to Patrick Handscombe for making Gerald Daly's text available. Patrick has researched the Clifton Rocks Railway and can be contacted using this address (make the obvious changes!) patrick DOT handscombe WHO'S AT btopenworld DOT com.